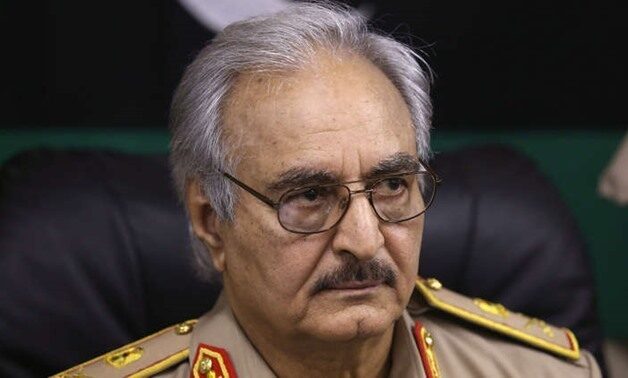

GADDAFI’S DOWNFALL August 2003. The Libyan envoy to the United Nations, Ahmed Own, delivers the following letter to then President of the UN Security Council, Syrian Ambassador Mikhail Wehbe:...

Latest news

BEYOND THE DEAL ON THE IRANIAN NUCLEAR PROGRAM: CONCERNS AND...

THE DILEMMAS FACED BY US FOREIGN POLICY IN THE MIDDLE...

IS THERE A SOLUTION TO MOROCCO’S SAHARAWI PROBLEM? For...

On May 6th, 2009, the first repatriation of illegal immigrants...